I was going to make this post earlier but was waiting to gather more information from field visits and growers. Most of you should be done harvesting by now and start to look at numbers on receipts. Without looking at receipts, it is probably a known feeling about yield reduction during harvesting time. I heard yield reductions ranging from 30% to 60% from different growers. A single event is unlikely to cause more than 50% yield loss (but still possible, like the 2018 frost), but we have a lot of events happening this season. Each of these events could contribute to a 10-15% yield reduction, and it also depends on where your fields are located and what kind of microclimate zone you are in. This year, the wild blueberry crop stages, pollination weather and management activities are very different from region to region. It is an interesting year for sure.

After visiting fields during harvesting season and talking

to growers and combining information we know throughout the season, I like to

summarize all the negative factors I know that contributed to yield losses this

year.

If you have additional points to share, please contact me.

Winter Weather

-

February 2023 “Polar Vortex”

As many of you already submitted the “Polar

Vortex” information related to wild blueberries, it is getting clear that this

event would have caused damage to blueberry overwinter stems, internally and

physiologically. Due to the lack of snow coverage in fields, and the extremely low

temperatures for a couple of days (Feb 3-5), stems and fruit buds could have

been damaged or with lower vigour for further development. Stems could also

have a lower tolerance to cold temperatures, disease, and insect damage. However,

if you are in a more protected area or with snow coverage in whole or parts of

fields, you wouldn’t experience a higher loss from the “Polar Vortex”. That’s

one of the reasons why within the same field, growers had some very good

patches mixed with very poor patches (barely any berries) (Figure 1).

Figure

1. A blueberry patch with good and bad sides

According to this Quebec

wild blueberry factsheet, overwinter rhizomes and stems will get damaged

when temperatures fall below -25°C. Around this temperature, sufficient snow

coverage is needed to protect plants and unfortunately, we didn’t have that condition

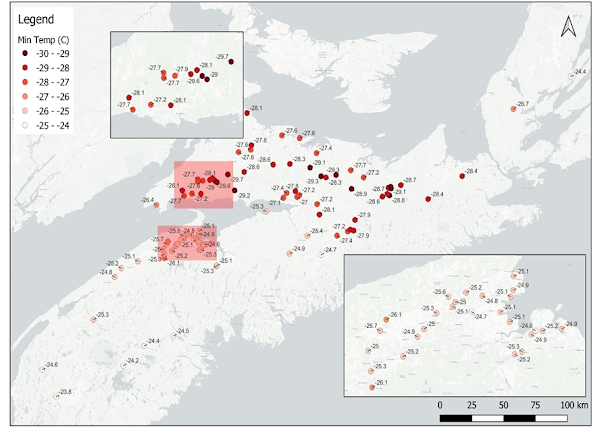

for most of the fields. When we checked all on-farm weather stations in NS, the

minimum recorded temperatures were below -25°C for most of the wild blueberry

stations in the northern region. When considering wind effect (wind chill and

wind speed), the damage level would be higher. Figures 2, 3, and 4 show the

minimum temperature, min wind chill and maximum wind gust from weather

stations. Click on each photo to see more detailed numbers.

Figure

2. Min Temp – Feb. 4, 2023 (NSDA/Perennia Weather Station Network, 96 Sites)

Figure

3. Min Wind Chill – Feb. 4, 2023 (NSDA/Perennia Weather Station Network, 96

Sites)

Figure

5. Max Wind Gust – Feb. 4, 2023 (NSDA/Perennia Weather Station Network, 96

Sites)

-

Below-average snowfall

We knew the lack of snow coverage in fields,

which resulted in a lack of protection for plants to fight cold and extreme temperatures.

The amount of snowfall, according to the National Agroclimatic Risk Report, was

below average and some areas of the region reported a record-breaking lack of

snowfall.

-

Warmer temperatures- not enough chilling hours

for wild blueberry plants

Before we talk about how warm this past

fall and winter were in NS compared to the more normal temperatures we were

supposed to get, let’s talk about chilling hours for blueberries.

Chilling

requirements for blueberry plants:

Blueberry plants require a period of cold

weather during the winter months, known as chill hours or chilling

requirements, to successfully produce fruit in the summer. This need for chill

hours is a biological adaptation that helps blueberry plants synchronize their

growth and fruiting cycles with the changing seasons. Adequate chill hours are

important for dormancy regulation, bud development, timing of flowering, as

well as fruiting and pest control.

We have limited information on wild

blueberry chilling requirements in terms of numbers, so we use numbers from

highbush blueberry production to interpret the warm temperatures we got in the

fall and winter and their effects on blueberry growth and yield potential. The

traditional definition of a chill hour is any hour under 7.2 °C. The mid-range

chill hour requirement for highbush blueberry varieties is between 500-550

hours. The wild blueberry is a high-chill plant, therefore it requires higher chill

hours. In other words, wild blueberry plants need to get at least 500-550 chill

hours for a successful fruiting year.

If crops do not get enough chill hours, you

may have to deal with problems of delayed foliation, bare shoots, weak bud

break, and even flowers that just fall off (shorter flower pollination life),

fruits that never develop, increased risk of pests and diseases, or poor-quality

fruit. One thing I heard commonly from growers is that it seemed that there were

a lot of blossoms (even more than ever), but there were no fruits. The chilling requirements for blueberries explain part of the reasons for growers' observation.

I wish I could present you with data and

numbers, but I am waiting for those numbers to come. I hope to update you on

this in the fall meetings. However, just based on how we felt in the fall, experienced

a warm January. I remember some growers applied Kerb at this time.

In normal years, regions in NS could start counting

chill hours as soon as we hit the first fall frost, but this winter, the date

to count consistent chill hours was much delayed. In the fall, if temperatures

drop below 7.2 °C for a few days, but suddenly back up to high temperatures, the

process can be reversed and we get a new start date and chill hours counting starts

over again.

The remaining factors are all related to rain and wetness.

Here is a nice graph that I got from CBC which shows the

amount of rain received in most wild blueberry fields in NS was 600- 800+ mm.

This is 2.5 times more than the average. Those rain events we got this year

either showed up at a bad time (pollination period), brought higher than the

average amount of rain, or had the intensity of rainfall in a short period. A

lot of times, we got them all this year.

Weed competition

Weed management starts early but runs for the whole year. It

is a never-ending task. Weeds are plants and watering plants makes them grow faster

and more. Herbicide application requires relatively dry conditions during

spraying but it will get benefits for some moisture in the soil to improve

herbicide efficacy after spraying.

-

Pre-emergence herbicide application

This point is not related to this year’s crop directly, but

it might impact next year’s crop if poor weed management was performed this

year.

Although April and early spring were fairly dry, we got a

break from the April drought at the end of April. I followed on fields owned by

growers who consulted me with blueberry emergence GDD and progress, a lot of

fields in the early Cumberland areas can start pre-emergence herbicide as early

as the last week of this April. I also noticed fields that received herbicides on

time before the rain had better weed control when fields were visited again in

mid-summer.

A lot of growers are still relying on their memory to plan

for spring herbicide timing which might put them in a bad position. We had a

very windy spring and early summer. On a lot of days, the wind speed and gusts

were above 30 km/hour. The first two weeks of May were the period when I knew

most of the growers were rushing to apply herbicides but also wanted to do fungicides

for mummy berries. We didn’t get mummy berry infection this year because it was

dry during early- mid-May. This is good for disease control but for herbicides,

if the soil were dried up quickly in the first few inches of the soil where are

wild blueberry root and rhizome system located, as well as most of the common

weed species growing zone, the control result could be reduced.

I also visited some sprout fields treated with Velpar

(hexazinone) this spring, and the control result was disappointing. Please

remember, that we have been using Velpar or Pronone since 1982 and in 40 years,

the repeated use of Velpar resulted in herbicide resistance in many weeds, such

as Red Sorrel and Hair Fescue. If you continue to use Velpar but in mid-summer,

if you still see a lot of weeds in your sprout fields, it is a good sign that

you need to switch to different products based on the weeds you have.

-

Weed growth in the summer- crop fields

Herbicide application in crop fields is limited due to fewer

products to use and the window to apply herbicides is short. This season, the

condition is favourable for weed growth which increases crop and weed competition.

Botrytis

This year, we had higher-than-normal botrytis blossom

infection across the whole province. It didn’t look like the damage was

significant or in a higher percentage yield reduction range, but those infected

fields and clones can expect 5-10% losses.

Several factors contribute to higher botrytis infection. During

the bloom period, rain never stopped in June. Excess moisture will increase

disease infection. Even though you are not in a foggy area or botrytis-prone area,

the wet conditions in every field make plants susceptible to infection. Weather

conditions (high wind and rainy days) also prohibited spraying fungicides so

many crop fields were under wet conditions without fungicide protection.

Pollination Weather

It was wet and cold during pollination and bloom period.

Some early fields had a few good pollination days before June and some fields

were lucky to have better pollination results either because of good weather or

higher pollination input. Overall it was a poor pollination year for wild

blueberries. The percentage of yield losses due to poor pollination was

variable from region to region since the weather was different in different

fields. The level of pollination input also has gaps between farms.

Excessive Wild Blueberry Vegetation (leaves) Growth in Crop Fields

A lot of you probably noticed that there were new blueberry

leaves formed and continued to grow before harvesting. This is more common and

severe to see in fields that receive high rates of granular fertilizer and

extra liquid fertilizer in both years. The wetter soil creates a good

environment to make soil nutrients and applied fertilizer more accessible for plants,

including blueberry crops and weeds.

When nutrients and energy are used to produce more

vegetation, the process of fruit development will be affected. Ultimately,

fewer berries are formed, and growers experience significant yield reduction. The

winter weather conditions and excess water and nutrients for plant growth

changed blueberry plants' physiological development.

More water after the fruit development stage

During the fruit development stage, it was one of the good windows

this year for wild blueberries. There was enough moisture and good temperatures,

so we observed bigger berries and crop fields started to turn in a better

direction. However, as we headed into the harvesting season, water started to

create problems.

-

Berry losses and quality

Too much water also made berries split

easier which reduced yield and fruit quality.

-

Harvesting weather and ground

During harvesting, the weather mixed a few

periods of rainy days in between which caused delays to harvest berries. Roads

in fields were soft and might have been washed out during flood events. Wild

blueberry fields’ ground was soft which reduced harvesting speed. Harvesters

and other machines’ tire tracks caused damage to the ground and potentially,

those areas will become wet spots in the future if not fixed.

What about this year’s sprout fields?

Similar to crop stems, sprout stems also continue to grow

vegetatively (more young leaves are produced). This delays plants’ tip dieback

(stopping point for blueberry vegetative growth), and next year’s fruit bud

forming and development. I also noticed fewer fruit buds were formed compared

to previous years. There are still a lot of time and unknown factors that could

affect next year’s crop and this is the biggest one I observed during farm

visits.

Plant vigour can also be affected by excessive moisture and water-logged

soils and this might hurt next year’s yield potential.